At a time when India is aiming to become an industrial powerhouse and a $5-trillion economy by 2026-27, the country’s nearly 500-million workforce, the second largest after China, lives in deep uncertainty over life after retirement. The minimum pension continues to be Rs.1,000 per month for the last two decades despite pre-election promises by national political parties for its upward revision. The inflation rate in India between 1999 and now has been 319.58 percent. This means Rs.1,000 in 1999 are equivalent to Rs.4,195.80 in 2023. The industrial pensioners are being clearly robbed in India. The pension system has practically no connection with the growing cost of living. There are over 60 lakh subscribers of the Employees’ Pension Scheme. More than 40 lakh members get pension less than Rs.1,500 every month. India ranks 40th out of the 43 pension systems globally while the government and industry often brag about the country’s position as the world’s fifth largest economy after the US, China, Japan and Germany.

The government and industry seem to be totally unconcerned about the plight of industrial workers after their usual retirement age of 58 to 60. The organised sector of industry is pushing to extend the retirement age ceiling to 65 years. Business-wise, it makes sense as companies can delay the payment of retirement benefits like gratuity and also bring down the pressure on their cash outflows. Unlike the latest spate of protests in France over President Emmanuel Macron’s decision to push the retirement age from 62 to 64, workers in India will gladly accept the industry’s move to raise the retirement age to 65 or more mainly due to the existence of a poor industrial pension scheme. In Germany, the retirement age is being increased gradually to reach 67 years by 2029. J.P. Morgan’s establishment in India, which has 50,000 employees, has raised its retirement age to 65 years, up from 60. In many advanced countries, life begins after retirement, when senior citizens look for leisure, long holiday travels and pursue finer interests.

In India, there is no system of periodical revision of its industrial workers’ pension. The country needs to undertake strategic reforms to revamp the pension system to ensure adequate post-retirement income, pointed out the 2021 Global Pension Index report. The country’s Employees’ Provident Funds Scheme is 70-year old. In 1976, the government started the Employees’ Deposit Linked Insurance Scheme. The Employees’ Pension Scheme came much later in 1995. The employer and employee both contribute @ 12 percent of wages towards the provident fund. Employers also contribute to Employees’ Deposit Linked Insurance scheme @ 0.5 percent of wages. The fate of the victims of industrial accidents, including those with permanent disabilities, remains mostly unknown. Industrial accidents kill hundreds of people and permanently disable thousands every year. In 1921, Parliament was informed that at least 6,500 workers had died while working in factories, ports, mines and construction sites in five years.

The statistics on the country’s industrial workers are not even reliable. They seem to differ from agencies to agencies conducting the surveys. According to a Labour Bureau survey, 3.14 crore workers were employed in nine organised sector industries in the December quarter of 2021. The number of workers stood at around 3.10 crore in the previous quarter. There is little information around how many workers retire or lose jobs every quarter. As per the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) carried out by the National Sample Survey Organisation of the Ministry of Statistics & Programme Implementation, in 2017-18, the total employment in both organised and unorganised sector in the country was around 47 crores. Out of this, approximately nine crores were engaged in the organised sector and the balance of 38 crores in the unorganised sector. The workers were divided into three categories — establishments with 10 or more workers; those with 20 or more workers and others engaged in the unorganised sector. If the number of employees under an employer is less than 20, he is exempt from PF registration for its employees. The question of contributory retirement pension does not arise for such employees. There exists a National Pension Scheme for traders and self-employed. Subject to several conditions, the pension ceiling is Rs.3,000 per month.

India’s rapid global economic growth rate is not translating to the quality of life of its vast workforce, organised or unorganised. The future of workers after retirement looks even more bleak with the shrinking employment in the organised sector. The growing trend of the contract labour system has little provision for pension, provident fund and gratuity. Even the government jobs at the centre and states are being created increasingly on a contractual basis. The duration of such jobs is normally around four years. A small section of such employees can expect an extension of service strictly on the basis of annual assessment reports. More and more companies are recruiting on contract basis through walk-in interviews. Remunerations are normally low. The job market has always been pro-employer due to massive unemployment in the country, which is expanding with population growth and higher access to education. From a six percent unemployment rate in 2017, India’s unemployment rate climbed to 8.3 percent in 2022. According to an estimate, over the next four years, 10 million more people would join the ranks of the unemployed. The number of jobless people in the country is expected to be more than 22 crores in 2023.

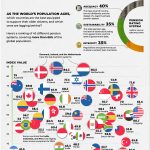

This explains why the pension of industrial workers occupies little priority in the government’s scheme of things. India never made a serious attempt to make sure that its citizens have adequate retirement income to survive gracefully. Countries such as the UK, USA, Australia, Canada and Malaysia are known to have taken different approaches to ensure that their citizens have adequate retirement income. Some countries even offer programmes for re-employment of retired workers as a means of providing its older citizens with more employment opportunities. India’s industry produced on an average a new billionaire every week in 2020, despite the Covid-19 pandemic, noted the 10th Edition of Hurun Global Rich List 2021, while the world’s most populous country’s retired industrial workers are forced to live on a pittance from pension schemes and other savings. (IPA Service)

The post Life Is Dreadful For Millions Of India’s Industrial Pensioners first appeared on IPA Newspack.