Singapore Air’s decision to restart direct flights to New York is an ominous sign for the future of aviation hubs like Dubai.

Singapore, Hong Kong, Los Angeles and Dubai became hubs from the 1970s to the 2000s for a simple reason: Commercial aircraft of the era struggled to travel more than about 10,000 kilometers without stopping to refuel.

That put swathes of the Americas off-limits to direct flights from East Asia, and meant travelers between Europe and Australia had to touch down in the Gulf or Asia en route. You can get a rough sense of the limitations by playing with this interactive map provided by Airbus.

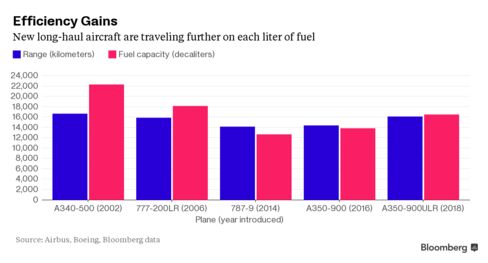

Technology is finally catching up. Fuel typically makes up about a quarter of an airline’s operating costs, and Boeing’s 787 and Airbus’s A350 have squeezed every ounce of benefit out of advanced materials and improved engine designs to use less:

That may mean geography isn’t destiny the way it was in the past. Southeast Asian airlines including Singapore Air, Malaysia Airlines and Thai Airways will be able to compete with Cathay Pacific and Emirates on North American routes, according to Capa Centre for Aviation, a consultancy. Qantas is considering direct flights between the Australian city of Perth and London, Air Transport World quoted Chief Executive Officer Alan Joyce as saying last week.

Being jammed into a pressurized tube for 19 hours at a time isn’t everyone’s idea of fun. Still, time-conscious executives whose companies are paying for lie-flat beds seem to love it. Singapore Air’s previous direct New York route, killed off in 2013 in the face of high oil prices, carried just 100 passengers in an all-business-class A340-500.

The likes of Singapore and Dubai will still have a role. Hubs allow airlines to serve a greater variety of destinations with fewer planes, as in the U.S. domestic market. Qantas added 25 European destinations to a previous tally of five by striking an alliance with Emirates in 2012.

But if business class passengers start migrating to the ultra-long-haul routes being opened up by Boeing and Airbus’s new designs, the hubs risk becoming conduits for lower-margin mass traffic.

That prospect will hardly be cheering for Singapore Air investors. The stock trades at 17.7 times forecast earnings, the highest valuation of any full-service airline in Asia, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. Its operating margin of 3.4 percent, meanwhile, barely scrapes into the top 20.-Bloomberg

![dubai flood is artificial rain behind uaes rare torrential weather[1]](https://thearabianpost.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/dubai-flood-is-artificial-rain-behind-uaes-rare-torrential-weather1-e1713378975696-550x550.jpg)

![2022 09 27T183330Z 84178340 RC2RJV9S1G6M RTRMADP 3 SAUDI POLITICS[1]](https://thearabianpost.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/2022-09-27T183330Z_84178340_RC2RJV9S1G6M_RTRMADP_3_SAUDI-POLITICS1-e1712223217759-550x550.jpg)