By Dr. Gyan Pathak

India has always been said to have great growth potential. In recent years, even the ‘fastest growing economy’ tag has been tied on its neck for several times. Now it is expected to retain this tag in 2023.Under the deception of such comforting propaganda lies the reality that the country is struggling hard to meet both ends meet for millions of its poor as it still houses largest number of poor in the world. The country falls in lower-middle income group on the basis of Gross National Income (GNI).

Presently 80 countries of the world are in the high-income group according the World Bank, while another 60 are in upper middle-income group. Lower-middle-income group countries are 47 in number and India is one among them. Only 31 countries are in low-income group. As per the Union Budget, Net National Income (NNI) per capita in India in 2022-23 was only around Rs 17,000.

A recent IMF working paper titled “Unleashing India’s Growth Potential” has analyzed the drivers of India’s growth in the last five decades, and considering baseline and upside scenarios of its medium-term potential growth, and concluded that only successful implementation of wide-ranging structural reforms could help support productivity and potential growth over the medium term.

The paper has used a production function approach to assess the impact of the pandemic on the key factors of production and therefore its impact on medium-term growth. It noted that the economic impact of COVID-19 on India has been substantial, with a decline in investment, employment, and productivity. While the recovery has been broad-based, there remain some gaps in contact-intensive services and micro, small, and medium enterprise (MSMEs) that were hard-hit by the pandemic.

Despite improvements in labour market conditions after the initial shock, employment outcomes for youth and women continue to lag, which was the case structurally prior to the pandemic. Reduced access to education and training due to the pandemic may have also held back improvements in human capita, adversely impacting labour market.

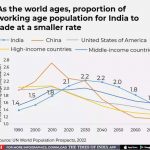

India’s growth drivers were Labour in 1970-1980s, capital in late 1990s and 2000s, and Total Factor Productivity (TFP) thereafter but prior to the recent economic slowdown, the paper has noted. However, despite rapid growth following the economic reforms, such as trade liberalization, domestic deregulation, and privatization, the scope of job creation was relatively limited, and labour force participation declined, especially among female workers.

While the growth rate of labour declined over the past 20 years, human capital growth has been relatively stable, the paper said. However, more recently, the slowdown in GDP growth before the pandemic was largely driven by slower growth in capital and TFP.

Importance of building capita in transitioning to higher-income economies is well known fact. India has also successfully accumulated capital stock over past decades, but continued investment are needed to further enhance India’s growth potential, the authors of the paper said. On the other hand, comparison also raises question of whether there are ways to further unleash India’s potential especially through labour and TFP channels.

On the baseline scenario, the paper found sever near-tern impact on the economy. Investment contracted about 10 per cent in 2020, more sharply than private consumption (-6 per cent) and overall GDP (-6.6) per cent. While investment rebounded in the following year, the sharp initial decline in investment subsequently affected capital accumulation. The paper noted the devastating short term impact on workforce.

The pandemic and containment measures significantly affected both employed persons and hours per worker, leading to a large decline in labour inputs. The impact was uneven and larger for the vulnerable, including casual workers, females, youth, and lower-skilled. About 60% of casual workers in urban areas lost their employment during the first wave and 30% during the second wave, which is about four to five times higher than that of self-employed and regular wage employees.

During the quarter following the peak of the pandemic wave, many unemployed people returned to employment as casual labour, which is the most vulnerable segment of the labour force. Analyses of employment trajectories showed that female, young, or less educated workers were more likely to lose employment during the pandemic. Migrant workers returning to their home villages transitioned into agricultural work or became unemployed, suffering from lower income. The labour market’s recovery from the pandemic shock is ongoing but remains uneven across sectors.

In the medium term, in the baseline scenario, the pandemic could affect potential growth through four main channels. The first one is capital input growth, through a contraction in investment. The second one is labour input growth, through a decline in employment and working hours. The third one is human capital stock growth, through disruptions to education and schooling, skills and on-the-job training. Finally, the pandemic could affect TFP growth through productivity.

In the first one, the paper noted the declining trend of the female employment ratio. Female workers in rural areas are reduced. Female labour force participation rate remained relatively low, which was only 26 per cent in India in 2017-19, and has significantly declined after the pandemic.

In the second one the paper noted the limited employment opportunity for youth. The economy did not generate enough job for young (aged 15-29) people despite improvement in education. Out of 44 million passed out only 10 million could find job. About 14 million struggled to find job, and 21 million focused on domestic duties. The fact that better educated youth had a higher unemployment rate also implies that there are structural mismatches in the labour market. Under the baseline scenario, employment is likely to increase, but with a successful implementation of reforms.

In the third one, limited medium term impact on potential human capital growth was projected. The impact of learning losses on the long-term growth rate could be substantial for India. Lastly, TFP growth will recover only with gradual recovery in labour productivity as the workers return from the lower productivity sector to higher productivity ones. During the pandemic they have migrated from the higher productivity sector to the lower productivity ones.

Considering the four preceding factors, the paper estimated potential growth of India in medium term to be about 6 per cent (2027) under baseline scenario, that too when presumed successful implementation of the reforms that could improve labour market functions.

This also holds good in upside scenario presuming the realisation of potential dividends of structural reforms on potential growth. The paper has emphasized that investment-friendly policies, including continued infrastructure investment and easing foreign direct investment regulation could help support capital accumulation and raise potential growth. On labour, the paper said that further reform is needed to improve female labour force participation and reduce unemployment, which would then help unleash the potential in India’s labour markets enabling the country to benefit further from its demographic dividend. Wide ranging structural reforms including in agriculture, land and business environment could help unleash India’s growth potential, it says. (IPA Service)

The post Realisation Of India’s Growth Potential Needs Better Support System first appeared on IPA Newspack.